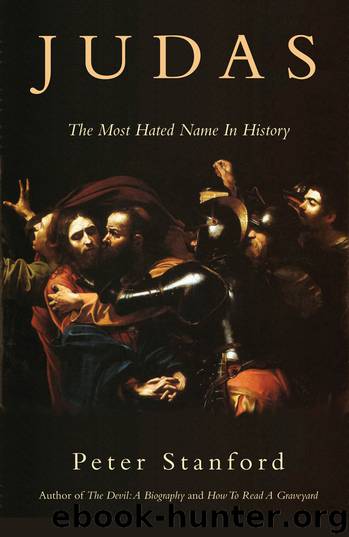

Judas by Peter Stanford

Author:Peter Stanford

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781619027503

Publisher: Counterpoint

Published: 2015-11-30T16:00:00+00:00

Money as the root of Judas’ evil

If bankers’ reputations are today regarded as being at a low ebb, reading Dante’s Inferno suggests there is further they could fall. Despite being the son of a banker, and the brother-in-law of a moneylender, he captures the widespread antagonism to the new rich in booming Italian cities when he consigns merchant-bankers to the seventh circle of hell, reserved for those who have committed crimes of violence and ‘other practisers of unnatural vice’, such as blasphemers and ‘sodomites’. That leaves them just two levels above Judas in the worst category of all: that restricted to traitors. It is, furthermore, a ranking that also damned them as worse sinners than inhabitants of higher levels that contain the lusty, the gluttons, the greedy popes and the angry politicians. Among those moneymen Dante specifically names and shames is Cavalcante de’Cavalcanti, the thirteenth-century Florentine who had lent money to the papacy on allegedly extortionate terms.

This wasn’t just Dante currying favour with the church, playing on the public’s prejudices, or creating scapegoats to make a point for his times to soothe his own disappointments in Florentine politics. In the internal debates of Catholicism, usury was very much a live issue. Thomas Aquinas, the thirteenth-century Italian Dominican theologian, still highly influential in contemporary Christian thought, was one of many to reflect deeply on the morality of usury as the rise of capitalism challenged traditional church teaching. And he did so by quoting the example of Judas. ‘It was from love that the Father delivered Christ, and Christ gave himself up to death; it is for reason that both are praised’, he wrote in his Summa Theologica. ‘Judas however delivered him out of avarice . . . which is why [he] has such a bad name’. Lending money might, in some cases, be licit, Aquinas conceded. What tipped the practice into usury and hence into sinfulness was when it was done with the same greed that Judas had demonstrated in betraying Jesus.

Judas’ central place in this whole debate about usury may explain why he is seen so much in Italian art of the period. In Assisi, in the Basilica of Saint Francis, the three-part cycle of frescoes on Jesus’ passion, death and resurrection, completed in the early fourteenth century, includes Judas in all five scenes of act one, the build-up to Jesus’ trial. As well as the episodes where he would have been hard to overlook (the betrayal and the Last Supper), he is also allotted a new and unwarranted (by the gospels) prominence, for example, among the followers of Jesus on his triumphant entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday. Judas stands at the front, next to Peter, as if both are the leaders of the apostles, though Judas, of course, has no halo.

That same juxtaposing of Peter and Judas is seen again in the depiction of the Last Supper, as Jesus gives Judas the sop of bread that marks him out as the traitor. Here Judas is no longer relegated

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Gnostic Gospels by Pagels Elaine(2493)

Jesus by Paul Johnson(2328)

Devil, The by Almond Philip C(2299)

The Nativity by Geza Vermes(2200)

The Psychedelic Gospels: The Secret History of Hallucinogens in Christianity by Jerry B. Brown(2135)

Forensics by Val McDermid(2065)

Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood, and the Prison of Belief by Lawrence Wright(1955)

Going Clear by Lawrence Wright(1935)

Barking to the Choir by Gregory Boyle(1805)

Old Testament History by John H. Sailhamer(1786)

Augustine: Conversions to Confessions by Robin Lane Fox(1752)

The Early Centuries - Byzantium 01 by John Julius Norwich(1712)

A Prophet with Honor by William C. Martin(1700)

A History of the Franks by Gregory of Tours(1699)

Dark Mysteries of the Vatican by H. Paul Jeffers(1690)

The Bible Doesn't Say That by Dr. Joel M. Hoffman(1663)

by Christianity & Islam(1604)

The First Crusade by Thomas Asbridge(1584)

The Amish by Steven M. Nolt(1544)